Battersea Power Station: Electrifying design

HIDE CAPTION

- Form meets function

- First proposed in 1927, the Art Deco Battersea Power Station initially drew criticism but has become a beloved London landmark, a monumental edifice of functional art. (Getty)

London’s Battersea Power Station has featured in films and on album covers. How did a once controversial building become so beloved? Jonathan Glancey reports.

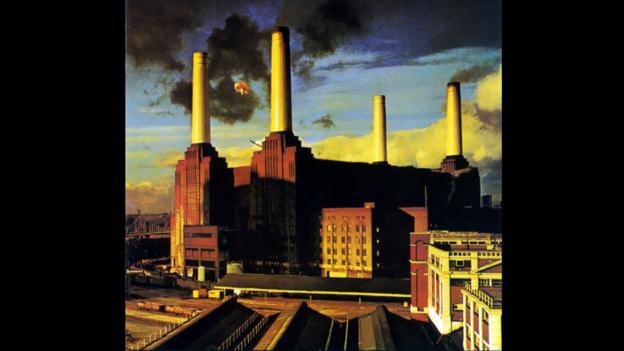

Algie was a 30ft (9m) pink pig who flew from Battersea to Kent where he scared local cows before being caught and returned to London. This bizarre occurrence took place in December 1976 when the design studio Hipgnosis was working on the sleeve for Pink Floyd’s tenth album, Animals. Together with the band’s Roger Waters, they came up with the idea of a shot of Battersea Power Station with a giant pink pig appearing to fly between the massive building’s fluted chimneys.

Made in Germany according to designs by Australian artist Jeffrey Shaw by Ballon Fabrik, a company that had once made Zeppelins, Algie was duly tethered to one of the chimneys, but broke loose. Watched by perplexed airline pilots descending into Heathrow, and chased by a police helicopter, the enormous pig took flight over south London.

The many fans of Battersea Power Station, a magnificent and daunting brick and steel structure built in two sections between 1929 and 1953, believe that its international fame owes much to Algie. Just as tourists keep photographing one another on the zebra crossing in St John’s Wood immortalised on the sleeve of the Beatles’ Abbey Road album, so visitors keep heading for Battersea hoping, perhaps, to see a pig fly.

Since the great, coal-powered power station closed for good in 1983, there have been many ‘pigs might fly’ schemes to revive it, as a theme park, a science museum, a 1,000-bedroom hotel – and now, after the sale of the building and the surrounding site to a Malaysian consortium, as the core of an ambitious housing and shopping scheme. No one is entirely sure what will happen in the future. What is certain is that few people have been in favour of demolishing Battersea Power Station.

Why? Because it is a thrilling, cinematic design, a building that caught the public imagination from the day it first opened in 1933, even though it only sported two of its four chimneys for its first twenty years. Built for the private London Power Company, and, from 1948, by the state-owned British Electric Authority, this compelling temple of power was a wonder of architecture and engineering as well as of science and technology: at its zenith, in the 1950s, it produced a fifth of all London’s electricity, with 28 smaller power stations providing the rest.

Nuts and volts

When it was first announced in 1927, there were fears that it might be a polluting eyesore. Some feared it could even damage paintings in the nearby Tate Gallery. There was no need for concern: the titanic turbines that produced all that electricity left nothing but plumes of white steam high over the London skyline. As children, we thought of it as a factory for making clouds. And even the most hardened commuters would lift their eyes from newspapers and paperbacks as their electric rush-hour trains threaded out from Victoria station and ran past the imperious power station. As for art and pollution, it was fascinating, decades later, to witness the conversion of Bankside Power Station further down the Thames into Tate Modern, Britain’s most popular art gallery.

The steel-framed Battersea building was designed by the engineers Sir Leonard Pearce and Henry Newmarch Allott with J Theo Halliday as architect of the Art Deco interior. Halliday’s opulent design, for the earlier half of the power station, rivalled that of the finest contemporary hotels, with walls lined in Italian marble and faience, with sculpted bronze doors, wrought-iron stairs and parquet floors. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect of Waterloo Bridge, Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral and the nation’s classic red telephone boxes, dressed the engineers’ steel frame in the highest quality brickwork, and gave the chimneys their eye-catching profile.

Listed as a heritage site since 1980, Battersea Power Station has been slow to find a new role. Property developers, their architects and proposals have come and gone, while rock bands, pop groups and singers, from Pink Floyd, Hawkwind and Judas Priest to Take That and Ayumi Hamasaki, have chosen the charismatic building as a promotional tool for their acts.

Filmmakers, too, have coveted the power station, from Alfred Hitchcock in his 1936 film Sabotage to Michael Radford and his adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984. The nightmarish Find the Fish song sequence in Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life was filmed in the Art Deco Control Room, and Algie the flying pig made a virtual return between the chimneys in the 2006 dystopian science-fiction film Children of Men; the image was later used in one of the films made for the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics.

With plans for an extension of London Underground’s Northern Line to Battersea and developers’ plans to restore the building and revitalise the surrounding property afoot, the power station might light up again. Whatever happens, it will never be a factory for making clouds or electricity again. Perhaps, though, someone may yet fly a celebratory replica of Algie some time towards the centenary of this great and popular monument.

No comments:

Post a Comment